-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 1

Introduction to RDF

RDF stands for Resource Description Framework.

- Well worth reading the RDF 1.1 Primer. This document supplements it and follows a similar structure.

- The Turtle spec describes a syntax for RDF which is well worth becoming familiar with.

- https://sketch.zazuko.com/ is a useful tool for visualising RDF.

- This add-on for RDF grammars in VSCode will help when writing RDF.

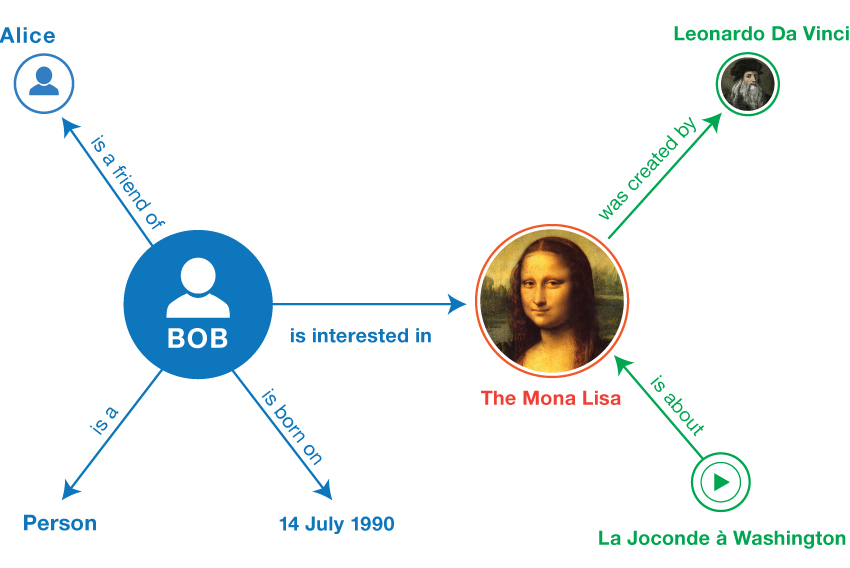

RDF statements are made up of triples. A triple consists of three parts - a subject, predicate and object. Many statements in English can be split up this way. By splitting statements into triples, we can represent them in a graph.

flowchart LR

Subject((Subject)) --Predicate--> Object((Object))

The statement Ross knows Alex can be represented as triples in this way:

- subject: Ross

- predicate: knows

- object: Alex

flowchart LR

Ross((Ross)) --Knows--> Alex((Alex))

To talk about things or resources using RDF, those resources need identifiers. These identifiers are typically called Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) and are similar to web addresses (URLs).

Usually, we pick our identifiers to be URLs. This gives the cool property that if you wanted to find out more about something with a particular identifier, you just need to put it into a web browser and you'll be able to find a webpage about it.

To represent the statement Ross knows Alex in RDF, we first assign identifiers to each of the things. For now, we'll make some up by prepending http://example.org# to each of the three parts of our triple. We end up with a graph which looks like this:

flowchart LR

Ross((http://example.org#Ross)) --http://example.org#Knows--> Alex((http://example.org#Alex))

While the URIs we have chosen contain names and English words, that doesn't need to be the case - we could have used ID numbers or something else. All that matters is that URIs are unique. Our data could look like this:

flowchart LR

Ross((http://example.org#12345)) --http://example.org#K99--> Alex((http://example.org#54321))

Wherever possible, we want to adopt identifiers which are frequently used. Many RDF vocabularies exist which define things like to know, and these are used to express relationships between different resources.

Really, the above example only states that some thing knows another thing, and both of those things have identifiers. We want to add additional information about these things.

Names and ages are best represented as strings and numbers. These are called RDF literals. Literals don't have identifiers. We can add additional triples to our data to provide more information about the resources with identifiers.

flowchart LR

Ross((http://example.org#Ross)) --http://example.org#Knows--> Alex((http://example.org#Alex))

Ross --http://example.org#Name--> ''Ross''

Ross --http://example.org#Age--> 100

Alex --http://example.org#Name--> ''Alex''

Alex --http://example.org#Age--> 200

Literals can only be the object of an RDF triple (i.e., you can't have a literal in the subject or predicate position).

RDF can be serialised in many different ways. We typically write RDF in Turtle and JSON-LD formats. We'll cover JSON-LD later.

A turtle file has an extension of .ttl. VS Code has an addon to make it easier to work with RDF filetypes.

The main syntax is:

- URIs are surrounded by

<and> - Literal strings are surrounded by quotes

" - Numbers are just raw numbers

- Comments are prefixed by

# - Statements end in a period

.

In Turtle, our most basic Ross knows Alex statement looks as follows:

<http://example.org#Ross> <http://example.org#knows> <http://example.org#Alex> .URIs appearing everywhere makes things verbose. We can assign @prefixes at the top of a turtle file as a shorthand. This also allows us to drop the angle brackets < >.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

ex:Ross ex:knows ex:Alex .Repeating triples which share a subject can be verbose. We can reuse the subject of a triple in a form of shorthand, separated by ;.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

ex:Ross ex:knows ex:Alex .

ex:Ross ex:knows ex:Andrew .

# is equivalent to -----------

ex:Ross ex:knows ex:Alex ;

ex:knows ex:Andrew .Where predicates are reused, we can separate objects with commas.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

# longhand ----------------------------

ex:Ross ex:knows ex:Alex ;

ex:knows ex:Andrew ;

.

# is equivalent to --------------------

ex:Ross ex:knows ex:Alex, ex:Andrew .The word a is used as a shorthand for the predicate rdf:type which has the URI http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#. It is used to indicate the type or class of a resource.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

ex:Ross rdf:type ex:Person .

# is equivalent to ---------

ex:Ross a ex:Person .Some strings have specific meaning, such as dates. To indicate a literal having a specific type, we use ^^ syntax followed by a URI representing the type of the literal.

Common datatypes are defined by the XML schema vocabulary, usually prefixed with xsd.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

@prefix xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#> .

ex:Ross ex:birthday "1900-01-01"^^xsd:date .In Turtle, plain strings and numbers are really typed literals.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

@prefix xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#> .

ex:A ex:B 1 .

ex:A ex:C 2.0 .

ex:A ex:D 4.2E9 .

ex:A ex:E "Hello World" .

# is equivalent to ------------------

ex:A ex:B "1"^^xsd:integer .

ex:A ex:C "2.0"^^xsd:decimal .

ex:A ex:D "4.2E9"^^xsd:double .

ex:A ex:E "Hello World"^^xsd:string .RDF string literals can have their language indicated in Turtle by an @ sign followed by a language tag. en (English) and cy (Cymraeg, Welsh) are most relevant to us.

As an example, books may have different names in different languages.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

ex:Q102438 a ex:Book ;

ex:name "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone"@en,

"Harri Potter a Maen yr Athronydd"@cy,

"Harry Potter à l'école des sorciers"@fr,

"Harry Potter und der Stein der Weisen"@de,

"Harry Potter y la piedra filosofal"@es ;

.Sometimes we want to refer to things, but we don't have an identifier for those things. Resources which we don't have an identifier for can be spoken about in RDF using blank nodes.

Consider the statement Ross knows someone, we can represent someone using a blank node, with square bracket syntax [].

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

ex:Ross ex:knows [] .We can provide more details about the blank node by supplementing predicates and objects within the square brackets.

So Ross knows someone whose name is Alex becomes:

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

ex:Ross ex:knows [ ex:name "Alex"@en ] .You can also create blank nodes by using the prefix _: followed by a blank node label which is a series of characters, so the above statement is equivalent to:

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

ex:Ross ex:knows _:Bnode123 .

_:Bnode123 ex:name "Alex"@en .Many RDF vocabularies exist to describe specific subjects. These vocabularies establish a common understanding of terms and encourage the reuse of identifiers.

RDF vocabularies will define properties - these can be used in the predicate position of a triple, and classes - which are usually used as the object of an rdfs:type statement.

Usually, properties (e.g. ex:knows) are lowerCamelCase and classes are UpperCamelCase (e.g. ex:Person).

Rather than each individual person coming up with their own definition of "to know" and creating its own identifier, we can adopt an identifier from a commonly known vocabulary. For example, the Friend of a Friend (FOAF) vocabulary has a property for foaf:knows at http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/knows.

When properties are defined, vocabularies usually specify what the intended class of the subject and object are (known as the range and domain of the property). For example, foaf:knows has a range of foaf:Person and a domain of foaf:Person, so should be used to form a relationship between resources which have the class foaf:Person.

We could rewrite our examples making use of the foaf vocabulary.

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

@prefix foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

# foaf:Person is a class.

ex:Ross a foaf:Person .

# foaf:knows is a property.

ex:Ross foaf:knows ex:Alex .Knowledge of vocabularies comes with experience. We make use of some domain specific ones, such as DCAT, CSVW, SKOS and RDF Data Cube (qb). Other well known ones include RDF Schema (rdfs), schema.org (schema) and Dublin Core (dcterms).

Turtle can be extended by another syntax known as TriG. TriG added support for graph syntax. The extension of a TriG file is .trig.

An RDF graph is a collection of triples. Sometimes, we might want to split our triples into different groups (like how data can sit in different tables), for example, to represent different sources of data. Graphs also have URIs.

Graphs are represented by a URI followed by braces { }, with all triples within a particular graph within those braces.

Triples which are not within a graph belong to the "default graph".

@prefix ex: <http://example.org#> .

@prefix foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

ex:Graph01 {

ex:Ross foaf:knows ex:Alex .

}

ex:Graph02 {

ex:Alex foaf:knows ex:Ross .

}Taken from the Related section in RDF 1.1 Primer - try to represent the following information in a Turtle file.

If you need to make up an identifier for something, use the http://example.org# namespace.

Try to reuse resources which have been defined in the Friend of a Friend (foaf) vocabulary.

Give each resource you create a class.